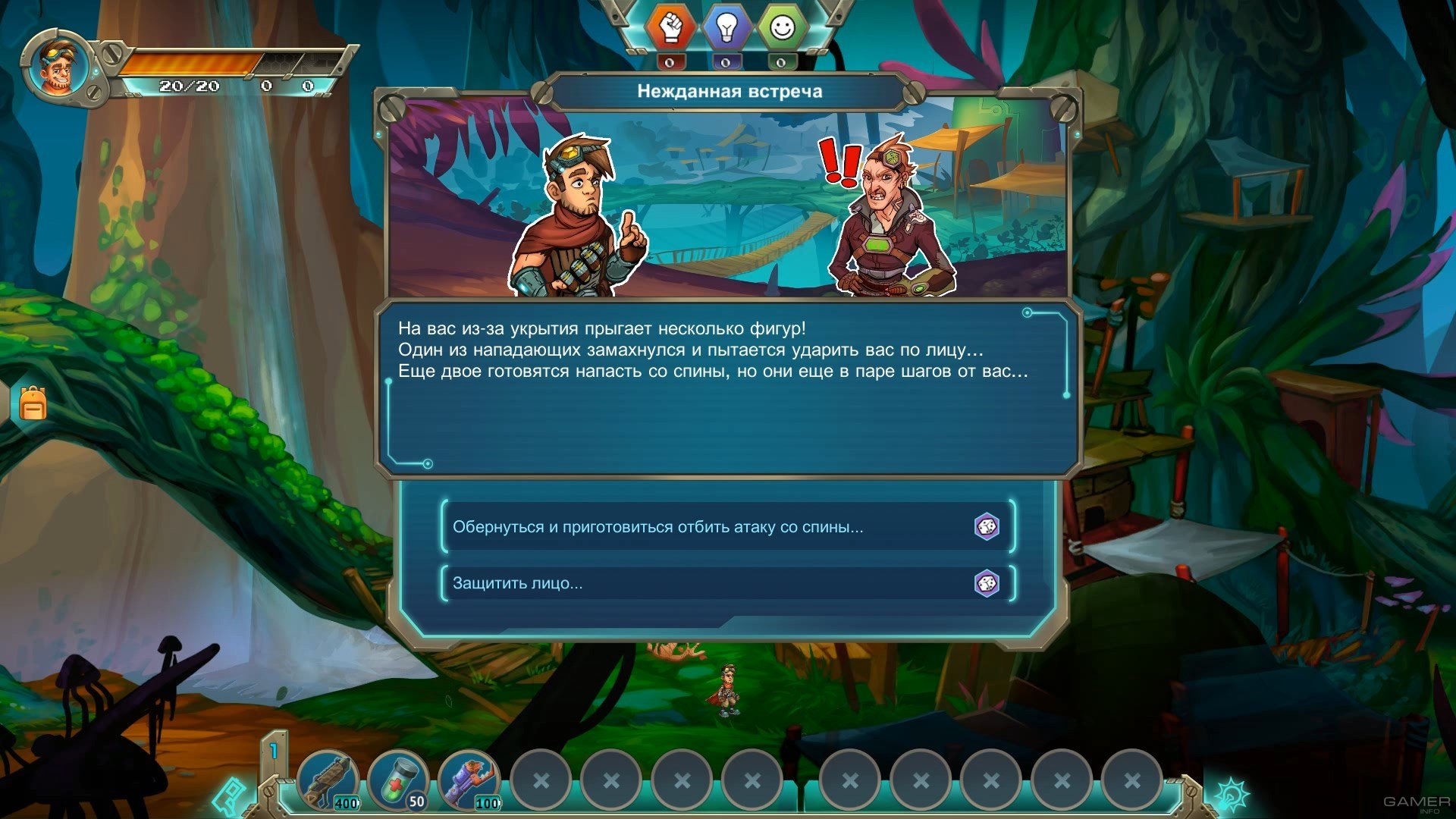

Join the journey of a funky space-archaeologist, who crashed on an unknown planet. A text, turn-based adventure RPG in which your choices actually matter. In astrophysics, an event horizon is a boundary beyond which events cannot affect an observer. The term was coined by Wolfgang Rindler. In 1784, John Michell proposed that in the vicinity of compact massive objects, gravity can be strong enough that even light cannot escape. At that time, the Newtonian theory of gravitation and the so-called corpuscular theory of light were dominant.

Star Story: The Horizon Escape 2017年09月05日 アドベンチャー カジュアル RPG インディーズ 2D Handdrawn Choices Matter Nonlinear Experience.

It's a popular misconception that black holes behave like cosmic vacuum cleaners, ravenously sucking up any matter in their surroundings. In reality, only stuff that passes beyond the event horizon—including light—is swallowed up and can't escape, although black holes are also messy eaters. That means that part of an object's matter is actually ejected out in a powerful jet.

If that object is a star, the process of being shredded (or 'spaghettified') by the powerful gravitational forces of a black hole occurs outside the event horizon, and part of the star's original mass is ejected violently outward. This in turn can form a rotating ring of matter (aka an accretion disk) around the black hole that emits powerful X-rays and visible light. Those jets are one way astronomers can indirectly infer the presence of a black hole. Now astronomers have recorded the final death throes of a star being shredded by a supermassive black hole in just such a 'tidal disruption event' (TDE), described in a new paper published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

'The idea of a black hole 'sucking in' a nearby star sounds like science fiction. But this is exactly what happens in a tidal disruption event,' said co-author Matt Nicholl of the University of Birmingham. 'We were able to investigate in detail what happens when a star is eaten by such a monster.'

'A tidal disruption event results from the destruction of a star that strays too close to a supermassive black hole,' said Edo Berger of Harvard University's Center for Astrophysics, another co-author. 'In this case the star was torn apart with about half of its mass feeding—or accreting—into a black hole of one million times the mass of the Sun, and the other half was ejected outward.'

AdvertisementDeath by tidal forces

The notion of being 'spaghettified' after falling into a black hole was popularized in Stephen Hawking's 1988 best-selling book, A Brief History of Time. Hawking envisioned an unfortunate astronaut who passed beyond the event horizon and would find themselves subject to the intense gravitational gradient of the black hole. (The gravitational gradient is the difference in strength of gravity's pull depending on an object's orientation.)

If the astronaut fell in feet first, for example, the pull would be stronger on the feet than the head. The astronaut would be stretched vertically and compressed horizontally by the black hole's tidal forces until they resembled a strand of spaghetti. From a physics standpoint, it's the same reason the Earth experiences tides: the gravitational pull from the moon pulls oceans one way and flattens them the other way. At least it would be quick; the whole process would occur in less than a second.

All of this is purely hypothetical, the subject of various thought experiments. But on the scale of stars and galaxies, a kind of spaghettification is a real phenomenon, albeit one that occurs outside the black hole's event horizon rather than inside. These tidal disruption events are likely quite common in our universe, even though only a few have been detected to date.

For instance, in 2018, astronomers announced the first direct image of the aftermath of a star being shredded by a black hole 20 million times more massive than our Sun, in a pair of colliding galaxies called Arp 299 about 150 million light years from Earth. They used a combination of radio and infrared telescopes, including the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA), to follow a particular formation and expansion of the jet of matter ejected in the wake of a star being shredded by a supermassive black hole at the center of one of the colliding galaxies.

AdvertisementHowever, these powerful bursts of light are often shrouded behind a curtain of interstellar dust and debris, making it difficult for astronomers to study them in greater detail. This latest event (dubbed AT 2019qiz) was discovered shortly after the star had been shredded last year, making it easier to study in detail, before that curtain of dust and debris had fully formed. Astronomers conducted follow-up observations across the electromagnetic spectrum over the next six months, using multiple telescopes around the world, including the Very Large Telescope (VLT) array and the New Technology Telescope (NTT), both located in Chile.

'Because we caught it early, we could actually see the curtain of dust and debris being drawn up as the black hole launched a powerful outflow of material with velocities up to 10,000 km/s,' said co-author Kate Alexander of Northwestern University. 'This is a unique ‘peek behind the curtain' that provided the first opportunity to pinpoint the origin of the obscuring material and follow in real time how it engulfs the black hole.'

According to Berger, these observations provide the first direct evidence that outflowing gas during disruption and accretion produces the powerful optical and radio emissions previously observed. 'Until now, the nature of these emissions has been heavily debated, but here we see that the two regimes are connected through a single process,' he said.

DOI: Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 2020. 10.1093/mnras/staa2824 (About DOIs).

Listing image by ESO/M. Kornmesser

Published May 2, 2019

Second of three parts

Lisa Mathis' idea of a normal childhood had long been skewed by the time a family friend got her loaded on cocaine and pimped her out to junkies at age 12.

Sexual abuse, addiction and dysfunction were woven into the fabric of life — along with soccer practice and big family parties, she said.

'I thought that was the way things were,' she said.

Mathis, now 39, worked for six pimps over the next 25 years, usually hooked on hard drugs and living among users. She endured a series of violent relationships involving men she had come to rely on. She spoke her mind at times of stress and had the battle scars to prove it.

Mathis is among the thousands of people whose lives have been disrupted or destroyed by the commercial sex trade in a southwest Houston neighborhood.

The overt sex trafficking in an area called the Bissonnet Track — mostly framed by Bissonnet, U.S. 59 and Beltway 8 — became so flagrant that local officials last summer sought a rare nuisance injunction aimed at preventing more than 80 suspected pimps, prostitutes and johns from conducting illicit business there.

Those people were public nuisances, according to the lawsuit, and could face fines if they were caught loitering in the zone.

The 'nuisance' list included Diana Kravetskaya, a 24-year-old Cypress woman whose beaten and meth-addled body was found behind a Dallas dumpster six months prior to the lawsuit. And Angel Peckham, who was recently dropped from the civil case, a week before she was found strangled in a vacant lot in east Houston.

Mathis wasn't on the list, though she'd worked as a prostitute on and off Houston's streets — including Bissonnet — for decades. Riley, who wouldn't give her age, was making the move to a minimum-wage job. And Kenya Latour, 38, known as Peaches, was working Bissonnet right before the lawsuit but avoided making the list.

The women's experiences, however, offer a unique perspective on the lives entangled in the underworld of prostitution in Houston. Their descent into the sex trade was shaped by early trauma, addiction and desperation. Their attempts to quit often veered onto detours that endangered their families, health and safety.

And while the proposed Bissonnet ban is meant as a deterrent, it is — to a degree — symbolic. No one disputed that many people making and spending money on commercial sex on the Track had escaped being named in the injunction. Few in 'the game,' as it's known, are aware the lawsuit exists, even those who put in years trudging the streets for a living.

Critics in the anti-trafficking community, however, said the lawsuit unfairly targets people who have survived abuse, abandonment and trauma and pushed them further toward the margins of society.

'When you talk about the women named on this injunction, you are talking about the weakest members of society who are most desperate for our help and may not ask for it,' said Ann Johnson, a criminal defense lawyer and former prosecutor who founded the human trafficking unit at the Harris County District Attorney's Office.

Lisa Mathis, 39, uses gentle detergent for her baby's laundry. Mathis told a support group late last year that he will be the first of her children she will parent. She said the baby is the first of four children who was not born addicted to opioids.

(Godofredo A. Vásquez, Staff Photographer | Houston Chronicle)'No other way out'Mathis was born addicted to drugs.

Her mother was hooked on sedatives, painkillers and muscle relaxants. Her father was a long-distance trucker who left his high-energy youngster to the care of his new wife and mother — strict disciplinarians who favored corporal punishment. Life was scarier and less predictable at her mother's place.

At 5, Mathis said, she was sexually assaulted by her mom's boyfriend. When a subsequent boyfriend of her mother's molested her at 9, she kept it to herself.

'I never said nothing about that .. but it happened,' she said. She had no barometer for normalcy.

Mathis lashed out at her step-siblings. At school, she threw a desk at a teacher. She recalled cutting class, smoking pot and partying with gang members at the bayou. A second stepmother pushed for Mathis to be admitted to a psychiatric facility, she said. She went to juvenile detention for breaking and entering. Then, she said, her mother sent her to stay with a friend.

The female friend introduced Mathis to cocaine and prescription drugs, she said. They went on benders for days. The woman started pimping her out, offering drug users 'dates' with the 12-year-old. The woman introduced her to crack at age 17. By 19, Mathis was dating a heroin dealer who became her next pimp.

Mathis, who used the street name Stacy, logged time in jail and a battered women's shelter. Amid the addiction, prostitution and incarceration, she gave birth to three children. Two were fathered by pimps, and all three were born addicted to opioids, taken into custody by Child Protective Services and raised by other people.

She made $1,200 or $1,300 a night on the Bissonnet Track tricking for a pimp named Mike. He'd park at the end of the block and wait for her to jump into a vehicle with a customer. He'd then follow her to parking lots, motels — even car dealerships — where they went for sex. He expected Mathis to text or call after the 'dates.'

'It made me feel safe, because you never know who you'll get in the car with,' she said. Mike, the father of one of her children, died in a car wreck in 2016.

Star Story: The Horizon Escape Crack Torrent

Certainly he wasn't the worst pimp she had. The most ruthless, by her account, was a guy she knew as Money. One time, Money smoked embalming fluid and in a paranoid rage pummeled her with a hammer, knocking out her front teeth.

'He was on drugs and he wanted to pimp me, and I wasn't giving him no money,' she said.

He once came close to pushing her off the Baytown bridge into the murky waters of the Houston Ship Channel hundreds of feet below. But another woman talked him out of it. Mathis hasn't been in touch with him in years.

Life without a pimp, however, could be worse. Her friend, Natalie Ochoa, a 31-year-old prostitute Mathis met working along Telephone Road, was beaten beyond recognition, strangled and left on a storm grate in southeast Houston. Her homicide case went cold for seven years before a suspect was arrested in 2018. The trial is pending.

Mathis survived her own brush with terror at the hands of a john while freelancing to fund her addiction. The customer held a knife to her throat and raped her, she said.

'I didn't want to die,' she said. 'I was in this man's vehicle and he beat me, you know? Who's going to even miss me for a few days if they don't see me?'

She made it out of his car alive. Crying, without her pants, purse or phone. But alive.

At age 32, she went into a recovery group with Kathryn Griffin, a former prostitute who specializes in helping women adjust to life off the streets. She made enough progress to travel with Griffin to California, where she was featured as a success story on a televised chat with Dr. Drew, a celebrity physician who specializes in sex and addiction.

Then she slipped back again, twice. Her life was chaotic, but prostitution provided financial stability, shelter and sustenance, she said.

It was hard to fathom another livelihood.

'There were times when I was terrified, but I had no other way out,' Mathis said.

Star Story: The Horizon Escape Cracked

'Where am I going to go?' she'd asked herself. 'What am I going to do?'

No one disputes that many people working on the Bissonnet Track were not sued by Harris County as alleged nuisances. Few in the area are aware the lawsuit exists. Photographed Thursday, Oct. 25, 2018, in Houston.

(Godofredo A. Vásquez, Staff Photographer | Houston Chronicle)Back to realityRiley began her descent into prostitution after being sexually abused as a child by a relative. She told family members but they didn't believe her.

'Why would they want to think about having a child predator inside their family?' she said.

Riley cycled in and out of CPS custody. Borderlands 2: siren glitter and gore pack download for mac. By sixth grade, she was sexually active.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/67061799/1166447451.jpg.0.jpg)

'I kind of knew it wasn't right,' she said. 'It didn't feel right, but I needed to get that attention.'

At 12 or 13, Riley ran away. She found a place to stay but she needed money. A woman who knew the Bissonnet Track became her first pimp, buying her clothes and taking her earnings.

'My first night out there I got raped by a trick,' Riley said. 'I didn't know what to do. I didn't know if that was normal.' She figured she couldn't call the police.

The johns would take her to motels by the Beltway, and she'd earn at least $800 a shift. Sometimes, she'd make $1,500 in a few hours.

Police collared Riley for petty theft and violating probation but rarely for prostitution because she knew how to avoid undercover cops. They were the guys who used proper words when they negotiated money and sex acts. Legitimate tricks always used code words.

And while the proposed Bissonnet ban is meant as a deterrent, it is — to a degree — symbolic. No one disputed that many people making and spending money on commercial sex on the Track had escaped being named in the injunction. Few in 'the game,' as it's known, are aware the lawsuit exists, even those who put in years trudging the streets for a living.

Critics in the anti-trafficking community, however, said the lawsuit unfairly targets people who have survived abuse, abandonment and trauma and pushed them further toward the margins of society.

'When you talk about the women named on this injunction, you are talking about the weakest members of society who are most desperate for our help and may not ask for it,' said Ann Johnson, a criminal defense lawyer and former prosecutor who founded the human trafficking unit at the Harris County District Attorney's Office.

Lisa Mathis, 39, uses gentle detergent for her baby's laundry. Mathis told a support group late last year that he will be the first of her children she will parent. She said the baby is the first of four children who was not born addicted to opioids.

(Godofredo A. Vásquez, Staff Photographer | Houston Chronicle)'No other way out'Mathis was born addicted to drugs.

Her mother was hooked on sedatives, painkillers and muscle relaxants. Her father was a long-distance trucker who left his high-energy youngster to the care of his new wife and mother — strict disciplinarians who favored corporal punishment. Life was scarier and less predictable at her mother's place.

At 5, Mathis said, she was sexually assaulted by her mom's boyfriend. When a subsequent boyfriend of her mother's molested her at 9, she kept it to herself.

'I never said nothing about that .. but it happened,' she said. She had no barometer for normalcy.

Mathis lashed out at her step-siblings. At school, she threw a desk at a teacher. She recalled cutting class, smoking pot and partying with gang members at the bayou. A second stepmother pushed for Mathis to be admitted to a psychiatric facility, she said. She went to juvenile detention for breaking and entering. Then, she said, her mother sent her to stay with a friend.

The female friend introduced Mathis to cocaine and prescription drugs, she said. They went on benders for days. The woman started pimping her out, offering drug users 'dates' with the 12-year-old. The woman introduced her to crack at age 17. By 19, Mathis was dating a heroin dealer who became her next pimp.

Mathis, who used the street name Stacy, logged time in jail and a battered women's shelter. Amid the addiction, prostitution and incarceration, she gave birth to three children. Two were fathered by pimps, and all three were born addicted to opioids, taken into custody by Child Protective Services and raised by other people.

She made $1,200 or $1,300 a night on the Bissonnet Track tricking for a pimp named Mike. He'd park at the end of the block and wait for her to jump into a vehicle with a customer. He'd then follow her to parking lots, motels — even car dealerships — where they went for sex. He expected Mathis to text or call after the 'dates.'

'It made me feel safe, because you never know who you'll get in the car with,' she said. Mike, the father of one of her children, died in a car wreck in 2016.

Star Story: The Horizon Escape Crack Torrent

Certainly he wasn't the worst pimp she had. The most ruthless, by her account, was a guy she knew as Money. One time, Money smoked embalming fluid and in a paranoid rage pummeled her with a hammer, knocking out her front teeth.

'He was on drugs and he wanted to pimp me, and I wasn't giving him no money,' she said.

He once came close to pushing her off the Baytown bridge into the murky waters of the Houston Ship Channel hundreds of feet below. But another woman talked him out of it. Mathis hasn't been in touch with him in years.

Life without a pimp, however, could be worse. Her friend, Natalie Ochoa, a 31-year-old prostitute Mathis met working along Telephone Road, was beaten beyond recognition, strangled and left on a storm grate in southeast Houston. Her homicide case went cold for seven years before a suspect was arrested in 2018. The trial is pending.

Mathis survived her own brush with terror at the hands of a john while freelancing to fund her addiction. The customer held a knife to her throat and raped her, she said.

'I didn't want to die,' she said. 'I was in this man's vehicle and he beat me, you know? Who's going to even miss me for a few days if they don't see me?'

She made it out of his car alive. Crying, without her pants, purse or phone. But alive.

At age 32, she went into a recovery group with Kathryn Griffin, a former prostitute who specializes in helping women adjust to life off the streets. She made enough progress to travel with Griffin to California, where she was featured as a success story on a televised chat with Dr. Drew, a celebrity physician who specializes in sex and addiction.

Then she slipped back again, twice. Her life was chaotic, but prostitution provided financial stability, shelter and sustenance, she said.

It was hard to fathom another livelihood.

'There were times when I was terrified, but I had no other way out,' Mathis said.

Star Story: The Horizon Escape Cracked

'Where am I going to go?' she'd asked herself. 'What am I going to do?'

No one disputes that many people working on the Bissonnet Track were not sued by Harris County as alleged nuisances. Few in the area are aware the lawsuit exists. Photographed Thursday, Oct. 25, 2018, in Houston.

(Godofredo A. Vásquez, Staff Photographer | Houston Chronicle)Back to realityRiley began her descent into prostitution after being sexually abused as a child by a relative. She told family members but they didn't believe her.

'Why would they want to think about having a child predator inside their family?' she said.

Riley cycled in and out of CPS custody. Borderlands 2: siren glitter and gore pack download for mac. By sixth grade, she was sexually active.

'I kind of knew it wasn't right,' she said. 'It didn't feel right, but I needed to get that attention.'

At 12 or 13, Riley ran away. She found a place to stay but she needed money. A woman who knew the Bissonnet Track became her first pimp, buying her clothes and taking her earnings.

'My first night out there I got raped by a trick,' Riley said. 'I didn't know what to do. I didn't know if that was normal.' She figured she couldn't call the police.

The johns would take her to motels by the Beltway, and she'd earn at least $800 a shift. Sometimes, she'd make $1,500 in a few hours.

Police collared Riley for petty theft and violating probation but rarely for prostitution because she knew how to avoid undercover cops. They were the guys who used proper words when they negotiated money and sex acts. Legitimate tricks always used code words.

Riley worked for five or six so-called finesse pimps, the types who controlled her with gifts and protection rather than outright violence. But then, one slashed her eyebrow and she quit working for him. She was sure another was the love of her life.

'I could have went home, but I was so in love with my pimp I didn't want to go,' she said. 'That was the mind control on his part. It's crazy when I think about it now. It's crazy how manipulative it was.'

Most Bissonnet pimps she knew had five or six girls working for them. She could tell who was working for so-called gorilla pimps — the brutal ones — because the women had black eyes or scars on their legs.

'I saw girls get their heads bashed into walls,' she said. 'One day I was out there and this pimp paid some of his homeboys to beat his girl with metal baseball bats. .. Bissonnet is the scariest. You never know what you're going to see.'

She finally got the courage to leave the streets but has had to rethink every aspect of her life — family, money, sex, men, relationships and coping skills.

'I had to be taught all over again, pretty much,' she said, 'because you lose all sense of reality when you're in that lifestyle.'

Working a regular job has been disappointing. And boring.

'I miss the adrenaline rush,' she said, referring to the jolt she experienced working high-dollar 'dates' on the Track.

'Sometimes it's hard for me to comprehend having a $7.25 (per hour) paycheck,' she said. 'I look at my paycheck and I'm like, 'What the hell? I'm on my feet the whole time I'm working and I get this? And then Uncle Sam takes out 25 dollars?'

'If I looked at my paycheck every two weeks,' she said, 'I would go back to the streets.'

(Godofredo A. Vásquez, Staff Photographer | Houston Chronicle)

- (Godofredo A. Vásquez, Staff Photographer | Houston Chronicle)

Kenya Latour was a child when she took to the street.

Her stepfather had been in and out of jail, and her mother was an addict. She blames her stepdad for that, too.

'He put the crack pipe in my mom's mouth,' she said.

She didn't know her father, so she sought attention elsewhere.

She never made the honor roll, but she was a solid athlete. A highlight of middle school was serving an entire volleyball game, 14 points straight, for the school team. But by 13, she began getting drunk and stoned and cutting class. About the same time, Latour began stripping at Houston clubs for extra money.

'I was living a fast life,' she said. 'I was selling dope. I was out in the streets a lot.'

She tried crack cocaine for the first time at 24. She wanted to see what was so great about it, why her mother had chosen that over her.

Crack reconnected Latour and her mother. For three years, mother and daughter lived in abandoned buildings and got high together, working the Bissonnet Track in Forum Park 'rain, sleet or snow' to keep the drugs coming.

Latour would hop in with customers while her mom served as lookout, jotting down the johns' license plate numbers. She says she never had a pimp.

'As long as the drugs are still out there, I don't see of a way of it being stopped,' said Tara M., who has struggled with crack addiction and used to serve as lookout for her daughter, Kenya Latour, on the Bissonnet Track. She came to Kathryn Griffin's group because Latour was missing.

(Godofredo A. Vásquez, Staff Photographer | Houston Chronicle)'You'd get into cars and you might be fine afterwards — or you might not,' Latour said. 'It's playing Russian roulette.'

One trick paid her then pressed cold metal to her temple. She figured it was a power trip. But after sex, he yelled at her to get out of his car or he'd shoot. She scrambled off, she said, and 'went straight to the dope man.'

The next assault was more violent. She thinks the man gave her syphilis because even shaded by tinted windows in his car, his face looked spotty. She said he whacked her in the face with the butt of a gun and assaulted her without a condom, keeping the pistol trained on her the whole time. He dropped her off without any money in an unfamiliar neighborhood.

How to get help

National resources

National Human Trafficking Hotline: Call 888-373-7888 or email at help@humantraffickinghotline.org to report human trafficking, get information about support services and learn about the warning signs of exploitation. Callers may remain anonymous.

National Center for Missing & Exploited Children: The center has an online CyberTipline and a hotline at 800-THE-LOST (1-800-843-5678) to handle reports of child exploitation, suspected abuse, online enticement of children, child pornography or child sex trafficking.

National Domestic Violence Hotline: Call 800-799-7233 for local resources such as emergency shelters, legal advocacy and assistance and social service programs.

Harris County

The Landing, 9894 Bissonnet St., #605: The faith-based drop-in center within the Bissonnet Track provides clothing, food, toiletries, counseling and case management. It is open Monday-Friday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., and can be reached at 713-766-1111.

Houston Area Women's Center, 1010 Waugh Drive: The center provides free advocacy, counseling, education, career support, help finding child care and case management, and has a food pantry and limited clothing available on site. The center serves men, women and children.

Domestic Violence Hotline: Call 713 528-2121 for help with emergency or transitional and 24-hour hospital accompaniment.

Sexual Assault Hotline: Call 713-528-RAPE (7273) for 24-hour hospital accompaniment for survivors of sexual assault.

Redeemed Ministries: The faith-based organization operates an eight-bed safe house and counseling program for sex trafficking victims in the Houston area. Referrals may be made online or via voice mail at 832-447-4130.

Harris County Pct. 1 Constable's Office: Call the human trafficking hotline at 832-927-1650 and leave a message for Kathryn Griffin or call the office's main line at 713-755-5200. Griffin accepts court-ordered participants as well as voluntary ones in her weekly support group. She has connections for shelter, education programs and more.

Latour was crying and bleeding outside a corner store when her dope dealer picked her up. The dealer took her to a local motel where she washed up and then headed back out to the block to earn more drug money.

'I didn't even get a chance to feel none of that,' Latour said.

It wasn't until she entered a program with Griffin at the Harris County Jail that it dawned on her that some of the johns had raped her. Even the trick who held a gun to her head didn't register as a rapist, she said.

'I thought it was all part of the ho game — you win some, you lose some,' Latour said.

She made it through five years of sobriety, helping Griffin and the FBI rescue trafficking victims in Houston. But everything came apart after she married a man she met at a treatment center — violating one of the basics of recovery by getting involved with another addict. He pulled a knife and tried to kill her, she said, and she cut him.

She was arrested and spent more than two months in jail. The assault charge was dismissed when she pleaded guilty on a drug charge and received deferred adjudication, a form of probation.

It was then she slipped back to Bissonnet, returning to her old spot on Sugar Branch and Forum Park. She had worked that corner for so long the kids used to wave to her from the school bus and greet her by her street name.

'Hey, Peaches!' they'd call.

'I'd tell them to keep their head up,' Latour said. 'Don't end up like me. Don't come out here. Don't do drugs.'

Last year, after failing to meet the terms of her probation, Latour was incarcerated on the drug charge. She is now serving a two-year sentence at the Plane State Jail northeast of Houston, where she attends one of Griffin's recovery programs.

Her arrests and addictions kept her from knowing her three children, but she's glad others stepped in to help. She blames her anger issues on her stepfather. And she's working on relationships with her counselor in the state jail. She knows now that she's not ready for one — that she doesn't have the capacity, she said.

'My pitcher is broke,' she said.

Kenya Latour, 38, who used the street name Peaches, said she worked the same corner for nearly a decade. She is currently incarcerated at Plane State Jail in Dayton, Texas.

(Godofredo A. Vásquez, Staff Photographer | Houston Chronicle)Simple pleasuresWhile incarcerated two years ago, Mathis promised her recovery coach for the third time she was ready to 'square up.'

It takes several attempts to fully leave the life, said Griffin, a former drug addict who runs support groups in and out of lockups. It took her 22 rehabs to go straight.

For now, Mathis is focused on being present for her fourth child, a cherubic 8-month-old boy named Versace. She launders his clothes in gentle detergent. She worries about his ingrown toenails and whether the tugging at his ear means he has an infection.

She wants him to have a real childhood, free from abuse and neglect.

'I don't want him to know hate and anger and rage,' Mathis said. 'We're not going to teach him that.'

Her first three children were born addicted to opioids. Last year, she saw her 19-year-old son for the first time since he was in diapers. She saw her now-5-year-old daughter only once in the infant room before she left the hospital. She keeps tabs on her 3-year-old daughter thanks to the child's adoptive mother, who posts pictures on Facebook.

She takes plenty of photos of her latest. A recent series showed Versace's pudgy hands gripping a Berenstain Bears board book, with an illustration showing a mother and father gently carrying two sleeping baby bears upstairs to bed.

The story felt ordinary and generic, even dull. Exactly the version of normal she hopes will come true for him.

Lisa Mathis, 39, is raising her son Versace along with his dad. Versace is the first of her four children born without an addiction to opioids.

(Godofredo A. Vásquez, Staff Photographer | Houston Chronicle)Part 1: Open-air sex trade permeates daily life on Houston's outskirts

Part 3: Cracking down: Advocates fight county's 'nuisance' lawsuit

Gabrielle Banks covers federal courts for the Houston Chronicle. She was part of the team that won an APME Grand Prize and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for breaking news coverage of Hurricane Harvey. The California native has been a criminal justice and legal affairs reporter for two decades, including staff work at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and the Los Angeles Times, and freelance work for the New York Times, the Mercury News, San Francisco Chronicle, New Jersey Monthly and the Miami Herald. Follow her on Twitter @GabMoBanks or email her at gabrielle.banks@chron.com.

Godofredo A. Vásquez is a staff photographer for the Houston Chronicle, primarily covering breaking news. Godofredo was born in El Salvador but grew up in the Bay Area, where he attended San Francisco State University and graduated with a B.A. in photojournalism. Before joining the Chronicle in early 2017, Godofredo spent two years working for the Corvallis Gazette-Times and the Albany Democrat-Herald in Oregon. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram at @godovasquez, or reach him by email at godofredo.vasquez@chron.com.

Design by Jordan Rubio and Jasmine Goldband

***